6.2. Convex Functions and Optimization#

An important result in optimization is that for a convex function, any local minimum is also a global minimum. This makes optimization problems with convex functions significantly easier to solve, since finding a global minimum is guaranteed once we find any local minimum.

A function \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}\) is convex if for all points \(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}\) in its domain and for all \(\lambda \in [0, 1]\), the following inequality holds

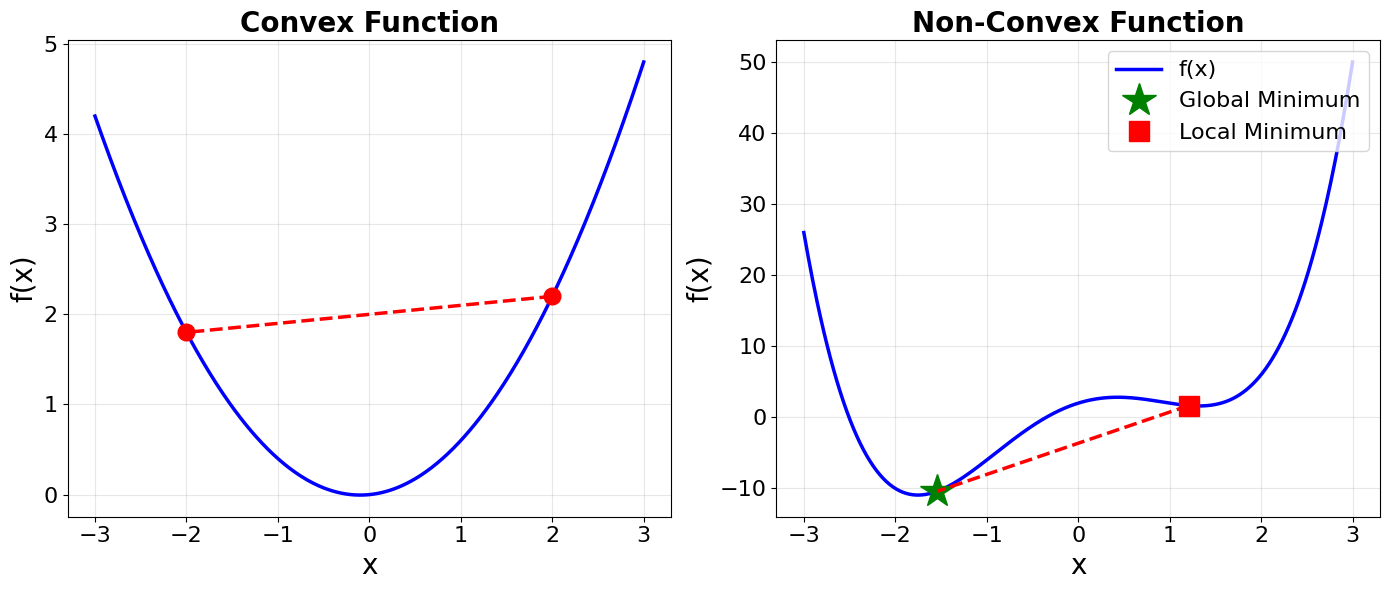

Convexity has a geometric interpretation. The left side represents the function value at a point on the line segment connecting \(\mathbf{x}\) and \(\mathbf{y}\), while the right side represents the corresponding point on the line segment connecting \((\mathbf{x}, f(\mathbf{x}))\) and \((\mathbf{y}, f(\mathbf{y}))\) on the graph. Therfore, a function is convex if and only if the line segment (called the secant line) connecting any two points on its graph lies on or above the graph itself. Below is a plot exemplify convexity. The left panel shows a convex function. The right panel shows a non-convex function.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create figure

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 6))

# ========== LEFT PANEL: CONVEX FUNCTION ==========

ax = axes[0]

# Define convex function

x = np.linspace(-3, 3, 500)

y = 0.5 * x**2 + 0.1 * x

# Plot the function

ax.plot(x, y, 'b-', linewidth=2.5, label='f(x)')

# Choose two points for the secant line

x1, x2 = -2, 2

y1 = 0.5 * x1**2 + 0.1 * x1

y2 = 0.5 * x2**2 + 0.1 * x2

# Create points along the line segment

lambdas = np.linspace(0, 1, 100)

x_line = lambdas * x1 + (1 - lambdas) * x2

y_secant = lambdas * y1 + (1 - lambdas) * y2

y_func = 0.5 * x_line**2 + 0.1 * x_line

# Plot the secant line

ax.plot(x_line, y_secant, 'r--', linewidth=2.5)

# Mark the endpoints

ax.plot([x1, x2], [y1, y2], 'ro', markersize=12)

# # Shade the region showing secant ≥ function

# ax.fill_between(x_line, y_func, y_secant, alpha=0.3, color='green',

# label='Secant ≥ Function')

ax.set_xlabel('x', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('f(x)', fontsize=20)

ax.set_title('Convex Function', fontsize=20, fontweight='bold')

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.tick_params(labelsize=16)

# ========== RIGHT PANEL: NON-CONVEX FUNCTION ==========

ax = axes[1]

# Define non-convex function with local and global minima

x = np.linspace(-3, 3, 500)

y = x**4 - 5*x**2 + 4*x + 2

# Plot the function

ax.plot(x, y, 'b-', linewidth=2.5, label='f(x)')

# Global minimum around x ≈ -1.54

x_global = -1.54

y_global = x_global**4 - 5*x_global**2 + 4*x_global + 2

# Local minimum around x ≈ 1.21

x_local = 1.21

y_local = x_local**4 - 5*x_local**2 + 4*x_local + 2

# Create points along the line segment

lambdas = np.linspace(0, 1, 100)

x_line = lambdas * x_global + (1 - lambdas) * x_local

y_secant = lambdas * y_global + (1 - lambdas) * y_local

# Plot the minima

ax.plot(x_global, y_global, 'g*', markersize=25, label='Global Minimum')

ax.plot(x_local, y_local, 'rs', markersize=15, label='Local Minimum')

ax.plot(x_line, y_secant, 'r--', linewidth=2.5)

ax.set_xlabel('x', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('f(x)', fontsize=20)

ax.set_title('Non-Convex Function', fontsize=20, fontweight='bold')

ax.legend(fontsize=16, loc='upper right')

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.tick_params(labelsize=16)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('convex_vs_nonconvex.png', dpi=150, bbox_inches='tight')

plt.show()

For twice-differentiable functions, convexity can be characterized using derivatives. In single variable calculus, if \(\frac{d^2 f}{dx^2} \geq 0\) for all \(x\), then the function is convex. This generalizes to multivariable functions through the Hessian matrix. A twice-differentiable function \(f\) is convex if and only if its Hessian matrix \(H(\mathbf{x})\) is positive semi-definite for all \(\mathbf{x}\) in the domain. This connection between convexity and the Hessian is particularly useful because it allows us to verify convexity by checking the eigenvalues of the Hessian. Since the Hessian is symmetric by definition, it has real eigenvalues. The matrix is positive semi-definite if and only if all eigenvalues are non-negative (i.e., \(\lambda_i \geq 0\)). If all eigenvalues are strictly positive (i.e., \(\lambda_i > 0\)), then the Hessian is positive definite, which corresponds to the function being strictly convex. For strictly convex functions, any local minimum is the unique global minimum.

The importance of convexity for optimization cannot be overstated. If \(f\) is convex and differentiable, then any point \(\mathbf{x}^*\) where \(\nabla f(\mathbf{x}^*) = 0\) is a global minimum. This means that gradient-based methods, which naturally find points where the gradient vanishes, are guaranteed to find global optima for convex problems. In contrast, for non-convex functions, gradient descent may converge to local minima that are far from optimal, or even to saddle points in high-dimensional spaces.

Many models in machine learning are convex. Linear regression with squared loss is convex because the objective function \(||\mathbf{y} - X\mathbf{\beta}||^2\) is a quadratic function with a positive semi-definite Hessian. Logistic regression with log loss is also convex, as demonstrated in the logistic regression notes where we showed that its Hessian is positive semi-definite. However, deep neural networks are non-convex due to the composition of nonlinear activation functions, this can make training them difficult.